Jan 29, 2015Consuming Questions

Our nutrition expert has helped solve dietary problems of all kinds, and has noticed that many athletes experience the same struggles. Here, she presents solutions to some of the most common sports nutrition dilemmas.

By Michelle Rockwell

Michelle Rockwell, MS, RD, CSSD, is a sports nutrition consultant based in Raleigh-Durham, N.C., who works with athletes and active individuals nationwide, including the varsity athletes at North Carolina State University. She and sports dietitian Susan Kundrat recently launched a new Web site dedicated to educating athletes, students, and health professionals on practical and proven sports nutrition strategies. She can be reached through the site at: www.rkteamnutrition.net.

An athlete comes to you with a quandary: He’s not taking in enough fuel for his intense practice and workout schedule, and he doesn’t know what to do. He is obviously stressing out about food, so much that you worry he might be in the early stages of an eating disorder. But after a long talk, you discover the real problem–he just moved off campus for the first time, and he has no idea how to cook.

When it comes to nutrition, what seem like simple, minor obstacles to you can vex even the most conscientious and dedicated athletes. At the high school and college levels, when individuals are adjusting to new personal freedom and responsibility, making wise decisions about food can be a major challenge.

Whether it’s eating right on the road, buying groceries on a shoestring budget, or finding ways to stay hydrated all day long, I’ve observed the same problems cropping up again and again when I counsel athletes on their nutrition habits. With the right strategies, you can help athletes overcome their challenges and fuel themselves for success.

EATING ON A BUDGET

For various reasons, many athletes have a limited amount to spend on food. A high school student’s family might be struggling to make ends meet, or a college athlete might be getting by on just a scholarship. Whatever the circumstances, tight budgets are a common reason why athletes short-change their nutritional needs.

When I work with budget-conscious athletes, my first question is an obvious one: How often do you eat out? It may seem like a no-brainer to adults, but many high school and college students don’t realize how much eating at restaurants (even cheaper ones) can cost them, and how easy it is to spend less.

With a smart shopping list, an athlete can buy ingredients for a whole week of healthy sandwiches for about the same price as one deli sandwich with chips and a drink. I have a client who started packing his lunch recently instead of eating out daily, and he saves over $100 per month!

Of course, preparing that smart shopping list may require some guidance. When athletes shop for themselves without help, they might end up living on a diet of mac and cheese, spaghetti, and ramen noodles–plenty of simple carbs, but not much else.

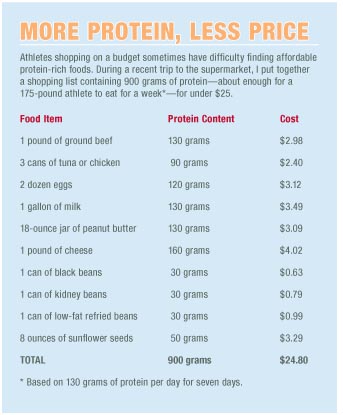

In my experience, protein is most frequently neglected when cost-conscious athletes do their own shopping, because many popular protein-rich grocery items–such as steak, fresh poultry, and mixed nuts–tend to cost more than other foods. But if an athlete knows what to look for, there are many inexpensive sources of quality protein. During a recent trip to my local grocery store, I found enough protein to meet the needs of a 175-pound athlete for a full week for less than $25. Check out “More Protein, Less Price” below to see how I did it.

Another common (and very pricey) grocery mistake is purchasing fresh produce out of season. A pint of blueberries, for example, costs around $1.99 in July, but $4.50 during winter. Produce tastes better and costs much less when it’s in season, so a quick handout for athletes on what’s best at each time of year can be very helpful. (See the “Resources” below for a downloadable one.) You can also recommend staple fruits and vegetables that remain fairly price-consistent all year long, such as avocados, bananas, lemons, limes, cabbage, carrots, celery, lettuce, onions, and peppers.

Some athletes spend an exorbitant amount on organic foods and beverages, thinking it’s a major investment in their health. There’s even a newly recognized eating disorder involving an unhealthy obsession with health foods: orthorexia nervosa.

To be clear, I won’t knock organics. The term refers to food and ingredients grown and processed in an environmentally friendly way with minimal use of chemicals, hormones, and preservatives, and those are certainly good ideas. But organic foods are typically more expensive, and the truth is, they’re not always worth it if money is tight.

For budget-conscious athletes who want to buy organic, I recommend focusing their organic purchases on the items most likely affected by chemicals during processing, such as apples, pears, potatoes, fresh meats, and milk. Packaged foods, such as organic breads, cereals, snack foods, and desserts should be a much lower priority. I have a client in recovery from orthorexia nervosa, and when I asked her to keep a food log that included all her organic purchases, we both chuckled at the inclusion of organic Oreos. Can anything in an Oreo be truly natural?

Here’s another suggestion that’s a big money-saver: Buy for quantity. Many athletes I know love the convenience of “100 calorie packs” and other easy-to-transport snacks. These are great for a between-meal carb and protein dose, but they are priced for their convenience factor and can be very expensive. Instead, tell your athletes to buy a large bag of granola, nuts, or crackers and put snack-size portions into small plastic bags. For example, a 16-ounce bag of almonds costs about $4, but 16 individually packed one-ounce bags total over $9. Same snack, lower price!

QUICK EATS

Many young athletes enjoy the convenience and low prices of fast food restaurants, and while they’re not traditionally thought of as places to eat healthy, it is possible to get decent, balanced meals if you know what to buy. There are several pieces of advice I always give athletes who tell me they eat fast food.

For one thing, price shouldn’t be the main factor when choosing a meal. Those value menu fries aren’t a smart choice just because they’re a cheap way to fill up. Instead of paying a higher nutritional cost in exchange for a lower financial one, an athlete should pass up the fries and spend an extra $2.50 on a second sandwich. It might cost more, but where would that money be better spent than on improving the nutritional content of a meal?

Fast food offerings are much more diverse than they used to be. Chili and a baked potato from the dollar menu at Wendy’s, grilled snack wraps from McDonald’s, and chicken soft tacos from Taco Bell are a few examples of inexpensive and relatively healthy options. Nutrition information is easy to find online at restaurant Web sites and other sites (see the Resources box for some examples).

Another easy way to save both money and calories at restaurants (fast food or otherwise) is by ordering water to drink. If an athlete eats out three times a week for a month and skips the soft drink each time, they can save over $25. That easily makes up for the extra spending on healthier “premium” salads or extra sandwiches in lieu of fries.

LOST IN THE KITCHEN

It’s amazing how many athletes go through high school and even college without knowing the basics of cooking. Maybe mom always prepared the family’s food, and then dining halls took over. One of my colleagues who works with athletes at all levels describes these individuals as “culinarily challenged.”

Providing athletes, teams, or whole athletic departments with a very basic cooking course taught by a registered dietitian can go far in solving this problem. In less than two hours, athletes can learn to prepare and cook three different meat entrees, three different starches, and three vegetable sides. Once an athlete has the basics down, he or she can be inventive and build on them.

Encourage teammates and roommates to work together on simple recipes, which can be found in cookbooks and literally hundreds of places online. Even if a 30-minute meal takes 45 minutes the first time, it’s great practice, and will increase the cooks’ understanding of what really goes into the food they’re eating.

Athletes also need to know that “cooking” doesn’t mean donning a poofy white hat and spending hours in the kitchen. Some consider microwaving a bowl of soup and putting together a sandwich to be cooking, and if the meal is healthy and the athlete enjoys it, that’s great. There are more healthy “heat and eat” options today than ever before, from basic one-minute brown rice and instant oatmeal to veggie-rich frozen skillet dinners and stir-fry meals. You can even find “just add chicken” or “just add beef” pre-packaged meals that don’t require any real cooking skills. As long as athletes read the labels to keep an eye on fat and sodium content, these can be great options for building a diverse and satisfying menu of home-prep meals.

VIVA VARIETY

It’s very common for athletes to eat the same foods every single day. This may occur as a result of over-simplified grocery shopping, limited dining hall preferences, or simply falling into a routine that tastes good.

You can probably guess why food monotony poses real nutrition problems. For instance, when athletes eat the same protein source every day–chicken, or eggs, or beef–to the exclusion of others, they most likely aren’t getting the full spectrum of amino acids that are critical for tissue building and repair. Vitamin and mineral deficiencies can also result from limiting food selections.

I recommend that athletes always choose a different type of meat or other protein with at least two meals each day. If they made chicken last night, today’s lunch could be a fish sandwich, and today’s dinner might be ground beef or a veggie burger. If they had eggs for breakfast, lunch might be something with a healthy serving of peanut butter, cheese, or yogurt.

Fruit and vegetable variety is critical for obtaining a good vitamin and mineral balance. Athletes who get in a rut of eating the same fruit every day for lunch and the same vegetable at dinner can miss out on important micronutrients. Encourage your athletes to rotate among at least three different fruits and three different vegetables at all times. It might be fresh banana, frozen strawberries, and raisins, plus steamed broccoli, spinach salad, and stir-fry mixed veggies (a great way to add extra variety). With this simple strategy, intake of nutrients and antioxidants will make a big leap.

Another great way to increase variety is to share meal duties with teammates. Once athletes have received that cooking instruction discussed earlier, everyone can develop a specialty, and team members can take turns making dinner for one another. Or two roommates can get in the habit of exchanging foods–half your bag of apples for half my pound of grapes–to add a little more diversity to the menu.

What about “picky eaters,” who don’t like a lot of variety in their diet? Oftentimes those barriers can be overcome with a little prodding. An athlete recently told me he didn’t eat pork and didn’t like any vegetables except green beans. As it turns out, his mother didn’t eat pork for religious reasons, and though he didn’t share her beliefs, he had just never tried pork products. Likewise, the only vegetable she had ever cooked for him was green beans. Once he branched out a bit, he found that he really enjoyed pork loin, and he ended up loving carrots, asparagus, and cauliflower.

Other times, picky eaters just need to make a few adjustments. Maybe an athlete thinks she hates broccoli, but when it’s prepared with cheese sauce or cooked into a casserole, she finds it quite tolerable and even enjoyable. And while we all remember that ketchup is not a vegetable, an athlete who doesn’t like tomatoes on sandwiches or salads might still enjoy pasta sauce or fresh salsa if it’s made with lots of spices and other flavors.

CONQUERING FAT PHOBIA

The term “fat phobia” became popular in the early ’90s when severely restricting fat intake was a common trend among athletes. I’ve noticed this trend resurfacing in many sports, and it’s a serious problem for some people. Very low dietary fat consumption can lead to poor immune response, slowed recovery, vitamin deficiencies, and menstrual issues in females. The American Dietetics Association and the American College of Sports Medicine recommend that athletes consume 20 to 25 percent of their calories from fat, and never less than 15 percent.

Fat helps food taste good, and athletes who place it off-limits will end up craving their favorite fatty foods. As a result, they’re much more likely to overeat or even binge on those foods when they let their guard down. Also, having some fat in a meal increases satiety (the feeling of fullness), which will curb the desire for unhealthy between-meal snacking. You should stress to athletes that moderation is the best approach.

More and more research points to the health benefits of eating plenty of unsaturated fats. Fish, oils, oily salad dressings, olives, avocados, hummus, nuts, seeds, flax, and peanut butter help the heart and improve inflammatory response. These natural sources of mono- and poly-unsaturated fats are more easily digested than the saturated and trans fats found in cookies, “junk food,” and other processed items. Many healthy fat sources are also rich in protein.

Omega-3 fats, found in a lot of those same foods, have been shown to positively affect mood, memory, and even joint health. Some new cheeses, eggs, yogurts, and fruit juices on the market are specially fortified with omega-3 fats, specifically docosahexaenoic acid (DHA, the most beneficial omega-3 commonly found in food products).

The best way to help a fat-phobic athlete is simply to educate them on the many health benefits of eating the right fats. You can tear down the notion that the term “fat” on a nutrition label translates into body fat by discussing the other key functions fat serves in an athlete’s diet.

For example, vitamins A, D, E, and K are fat soluble, which means they’ll only be absorbed by the body if accompanied by sufficient fat intake. So while an athlete may think they’re helping themselves by eliminating as many fat sources as possible, in fact they could be creating a serious vitamin deficiency. Vitamin A is important to eyesight and healthy skin and bones, vitamin D increases absorption of calcium and promotes hardening of bones and teeth, vitamin E is an antioxidant that prevents cell membrane damage, and vitamin K helps with blood clotting.

Recent research into vitamin D has also shown that a deficiency increases risk for stress fractures, which are a constant concern for athletes in many sports. In addition, a lack of vitamin D has been linked to chronic inflammation and autoimmune disorders. By shifting the focus away from preoccupations with body weight and toward the biological functions of fat, athletes can be convinced to take a healthier approach to dietary fat intake.

OFF-COURSE HYDRATION

Hydration has been a major buzzword in athletics lately (and for good reason), so most conscientious athletes have developed good hydration habits when in their normal training environment. But hydration problems can still plague them, and I’ve noticed it usually happens when their training location changes. For example, a swim team might have regular access to fluids at the pool, but they don’t have an easy, portable solution for when they do stadium runs or other dry-land drills outdoors.

One simple solution is for teams to assign the job of hydration coordinator to one person: an assistant coach, athletic trainer, team manager, or even a team member. Whenever the team will be practicing or working out away from their normal setting, this person is responsible for making sure there will be plenty of water or other beverages available at the site. Smaller teams might need just a cooler on wheels, while larger teams may require a hydration cart or other system.

Cross country athletes often have trouble staying hydrated during long runs, since they don’t want to carry a large water bottle with them. Teams and individual runners can benefit from mapping out their course ahead of time and having someone drop off a cooler, arrange for a water hose, or find another way to provide fluid at certain points throughout the course.

When athletes are running alone, they can plan a loop that will allow them to stop and drink at several places along the way. Bringing along a couple dollars is always a good idea if they’ll be running by a convenience store that sells bottled water.

Athletes who have trouble staying hydrated often say they drink plenty at meals, but don’t have time to seek out beverages with their busy class schedule and all their other activities. Try recommending that they throw a refillable water bottle into their backpack in the morning, and refill it a few times throughout the day at a drinking fountain. Once they get in the habit, they’ll find themselves taking swigs all day long. They will likely feel better and may even see a performance boost as a result.

COMMON THREADS

Most of the nutrition problems faced by today’s high school and college athletes aren’t complicated. They can often be addressed with a little planning and preparation. Your guidance in these matters doesn’t require advanced nutrition expertise, and the benefits of putting forth a little extra effort can be incredible.

Whether it’s creating a shopping list, assisting with prudent food budgeting, or just figuring out where water fountains are stationed along a running route, simple steps can provide a major boost to an athlete’s nutritional profile and overall health. And once an athlete has overcome their own hurdles and learned how to better prioritize nutrition, they’re usually amazed at how easy it is–and what a difference it makes.

Sidebar: RESOURCES

These Web sites contain information on the nutrition content of many foods found in restaurants and supermarkets:

To download a handout for your athletes showing when various fruits and vegetables are in season, go to: www.training-conditioning.com/ProduceGuide.pdf.