Aug 2, 2019Post-operative rehab following hip arthroscopy

Hip arthroscopy refers to the viewing of the intra-articular aspect of the hip joint with the use of a small camera, the “scope.” The procedures performed during hip arthroscopy can vary from simple debridement procedures to more extensive labral repairs and reconstructions as well as bone reshaping. Arthroscopy of the knee and shoulder has been performed for many decades, with the use in the hip beginning in the more recent past. In the past decade with the advances in surgical instrumentation and awareness of hip pathologies, there has been a period of rapid growth.

With the occurrence of hip arthroscopy rapidly on the rise, growing almost 500% from 2007 to 2014,1 the importance of a strong understanding of the underlying pathology and subsequent rehabilitation is crucial for the athletic training profession. Procedures performed during hip arthroscopy can be variable, however the most common underlying diagnosis or pathology that leads to the procedure are femoroacetabular impingement (FAI) and labral pathology. Byrd describes FAI as a morphological variant in the structure of the hip that predisposes the joint to intra-articular pathology that then becomes symptomatic.2 Pincer impingement is created by an overhanging rim of the acetabulum at the anterolateral aspect. Cam impingement is a result of a nonspherical head of the femur. Pincer and cam impingement can occur independent of each other or at the same time, described as mixed impingement. In the case of pincer impingement, most damage occurs to the acetabular labrum with potential secondary articular damage, whereas with cam impingement, damage to the articular cartilage typically occurs due to the delamination resulting from the out of round femoral head engaging with the acetabulum.

With the occurrence of hip arthroscopy rapidly on the rise, growing almost 500% from 2007 to 2014,1 the importance of a strong understanding of the underlying pathology and subsequent rehabilitation is crucial for the athletic training profession. Procedures performed during hip arthroscopy can be variable, however the most common underlying diagnosis or pathology that leads to the procedure are femoroacetabular impingement (FAI) and labral pathology. Byrd describes FAI as a morphological variant in the structure of the hip that predisposes the joint to intra-articular pathology that then becomes symptomatic.2 Pincer impingement is created by an overhanging rim of the acetabulum at the anterolateral aspect. Cam impingement is a result of a nonspherical head of the femur. Pincer and cam impingement can occur independent of each other or at the same time, described as mixed impingement. In the case of pincer impingement, most damage occurs to the acetabular labrum with potential secondary articular damage, whereas with cam impingement, damage to the articular cartilage typically occurs due to the delamination resulting from the out of round femoral head engaging with the acetabulum.

It is important to remember that the presence of FAI in the absence of pain or symptoms is a relatively common morphological occurrence. In 2016, the Warwick agreement3 stated the definition of FAI syndrome is a motion-related clinical disorder of the hip with a triad of symptoms, clinical signs and imaging findings. It represents symptomatic premature contact between the proximal femur and the acetabulum. Forced flexion, adduction and internal rotation is utilized as the impingement test as it relates to the reproduction of symptoms associated with impingement.

Ultimately, many of the activities that athletes participate in, both in their specific sport as well as in the weight room, create positions of impingement. In the presence of FAI, this can often lead to pain and dysfunction of the hip and pelvis. An athletic trainer can serve as the first line of defense in possibly preventing the need for hip arthroscopy or at the very least creating a prehab program to enhance the post-operative outcome. The first step in this process is the ability to identify a mobility deficit at the hip in an athlete. Far too frequently individuals are told they are “tight,” and they need to just stretch more. In the case of FAI or other intra-articular pathology, this may result in progressive pain and limitations for the athlete.

» ALSO SEE: An innovative type of ankle surgery

If an athlete is identified as having FAI syndrome or other intra-articular pathology that may be headed down the road of hip arthroscopy, the athletic trainer can play a vital role in activity modifications especially as it relates to strength and conditioning adjustments. In addition, they may develop a prehab program that maximizes the patient’s capsular mobility, soft tissue extensibility, and muscular strength and endurance around the hip to facilitate a more seamless post-operative progression. Ideally, movement dysfunctions such as poor pelvic control/stability and impaired movement above or below the hip should be identified and treated in the prehab programming as well.

Prior to surgical intervention, athletes with hip pathology should avoid positions of impingement when possible. This includes deep hip flexion, such as squats and lunges, as well as combined movements in to flexion with internal rotation or adduction. Deep flexion with the addition of a heavy load should be avoided, especially in the presence of pain. Other movements that will commonly facilitate increase pain are loaded pivoting and prolonged positioning. In some cases, these movements, loaded pivoting especially, cannot be avoided (think soccer, golf, tennis, pitching, etc.). In those instances, if the athlete is trying to continue competition, it is important to focus efforts on excellent dynamic control, aka get them as strong as possible within their limits to decrease the stress on the joint itself.

Once surgical intervention takes place, it is crucial that the entire rehabilitation team is knowledgeable on the process and timeline for expected recovery. Ultimately the precautions and timeline for return to sport are dependent on the procedures performed, however each athlete should be treated independently based on their individual progress with mobility, range of motion, strength, endurance and functional movement competency. The long-term goal following hip arthroscopy is full return to sport, at or above the previous level with little to no potential for re-injury.

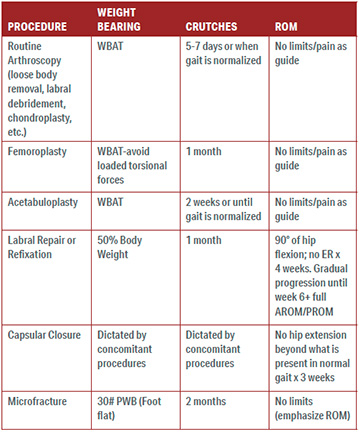

Basic weight bearing and range of motion restrictions for common hip arthroscopy procedures can be found in the TABLE 1.

Generally, the post-operative rehab following hip arthroscopy can be broken down into four phases. Each phase has a general yet fluid time frame that is associated with it. Athletes move within and between phases based on multiple criteria, some of which is dependent on their specific sport or position.

Repair/acute post-op phase (immediate post-op to one week post op)

This is the initial days following surgery where the main goals of rehabilitation are to control pain and effusion, and create an environment for early mobility within the surgical precautions. Basic modalities, including the use of vasopneumatic devices, can be very helpful in this phase for pain control. In addition, low grade mobilizations or simple long axis distraction can assist in pain control as well as decrease risk for adhesions.4 Basic exercises to facilitate activation of the lower extremity and stationary biking without resistance are typically initiated in this phase.

Common pitfalls of the repair phase include poor gait mechanics or avoidance of a foot flat gait progression. No matter what the procedure, patients should be encouraged to neutralize the ground reaction forces and ambulate with a normal heel-to-toe pattern to avoid over activation of the hip flexors during standing and walking. Even in the presence of microfracture, patients should be cautioned from holding the leg off the ground completely or utilizing a toe touch pattern. On the opposite end of the spectrum are patients who are overloading the surgical hip and, therefore, the healing tissues with too much or excessive weightbearing beyond the noted restrictions.

Rehab/recovery phase (three to seven days post-op to eight to 12 weeks post op)

In this phase, there is a focus on restoring normal mobility, range of motion (progressing as the precautions are lifted), muscle activation, strength, and functional abilities within activities of daily living. It is crucial that normal arthrokinematics are restored in this phase when possible. In the case where the extent of the damage will not allow for this, it is important that all treating clinicians are aware of this and have a plan to work around any specific limitations. In addition, it is important as strength is restored in the musculature around the hip including the core, that the patient is able to control and manage loading in multiple functional positions such as quadruped, kneeling and variable standing postures. Compensatory movement patterns should be identified and avoided during the progression of this phase.

Common pitfalls of the rehab/recovery phase include too soon or too much weight bearing activity beyond the patients muscular strength and endurance ability. Very commonly this phase results in one or two “honeymoon periods” where the patient is feeling very well and becomes over confident in their abilities. If not careful, the athletic trainer may make this same mistake and progress the patient beyond what they are ready to handle. This can be combated with frequent assessment and re-assessment of strength and kinematics before, during and after new or advanced activities are added to the rehab progression.

Reconditioning/return to training phase (12 to 20-plus weeks post-op)

This is the most variable and challenging phases of the post-operative rehab for athletes. In this phase, the athlete should be working on skill development, force and load volume tolerance, and management of recovery. Bridging the gap from the rehabilitation to the performance phase may take just a few weeks and upwards of a few months depending on the level of the athlete, the demands of the sport and position on the hip, and the procedures performed/damage identified intra-operatively.

It is important that the athlete be well informed through the entire rehab process, but especially during this phase as the balance between workload and recovery will be a challenge if they do not assist in giving feedback on how they are feeling. Use of technology such as sleep and heart rate monitors, accelerometers, and motion capture systems can assist in the development of this phase when available. The athlete should not be experiencing any pain, loss of motion or decrease in baseline strength as they progress in the reconditioning phase.

Common pitfalls in the reconditioning phase include premature advancement of stability and endurance challenges without appropriate movement patterns or trunk stability. In this phase commonly return to running may be a significant challenge if there is not appropriate muscular endurance, or if poor pre-surgery mechanics are not addressed. The use of video analysis by a trained member of the rehab team may be useful in combating some of these issues.

Performance/return to play phase (16-plus weeks post-op)

This is the time from return to team practice through the end of the season and some would say until preseason for the following season is completed. This is a variable process dependent on the specific sport and position. Ideally, if contact is involved, the player participates at their position taking reps at full speed with little to no contact and is gradually reintegrated into full return to unlimited play.

The two most common pitfalls as athletes return to play following hip arthroscopy are poor recovery planning/management and lack of adherence to a maintenance program as it relates to the strength and control of the muscles around the hip. The athletic trainer’s ability to keep these items in check as the player returns to sport is a critical aspect of successful return to sport.

Facing the challenge

Rehabilitation following hip arthroscopy of an athlete can be a challenging task for the athletic trainer dependent on a variety of factors. Certainly, an athletic trainer is capable in their skills and abilities to follow the recommended protocols. However, these patients frequently require extensive amounts of manual therapy interventions and one on one neuromuscular reeducation and strength progression that dependent on the athletic trainer’s setting, may not be realistic. For example, in a high school setting there may be one or two athletic trainers for the entire school handling all injuries across all sports. This is a very different set up than an NBA team with a multitude of medical staff and less than 15 athletes to care for.

It is not uncommon for athletes to be managed with a team approach following surgery, especially in the rehab and reconditioning phases. Typically, a physical therapist (PT) and athletic trainer (AT) team works very well for these athletes. The PT can manage the manual therapy needs as well as monitor the progression of motor control and strength development while the AT is able to spend more time in the progression of movement patterns and strength development.

Most importantly, when rehabilitating an athlete post hip arthroscopy, the key thing to remember is no one rehab progression is like the next. There are an incredible number of factors that go into the process and the entire rehab team as well as the athlete should be in constant communication regarding how the patient is progressing. Any setbacks along the way can typically be handled relatively easily when identified and addressed quickly.

References

- Truntzer JN, Shapiro LM, Hoppe DJ, Geoffrey D, et al; Hip arthroscopy in the United States: an update following coding changes in 2011, J Hip Preserv Surg. 2017;4(3):250–257. Link »

- Byrd, JW. 2013. Operative Hip Arthroscopy. In My approach to femoroacetabular impingement (pp. 215-235). New York, NY: Springer.

- Griffin DR, Dickenson EJ, O'Donnell J, et al The Warwick Agreement on femoroacetabular impingement syndrome (FAI syndrome): an international consensus statement. Br J Sports Med 2016;50:1169-1176.

- Willimon SC, et al. Intra-articular adhesions following hip arthroscopy: a risk factor analysis. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2014;22(4):822-5.