Jan 29, 2015To New Heights

The Hatch System has helped countless weightlifters win gold medals. Here’s how to make it effective for athletes in team sports.

By Melissa Moore Seal

Melissa Moore Seal, MS, is Associate Head Strength and Conditioning Coach at Louisiana State University, where she is responsible for training the women’s basketball and softball teams. During her time at LSU, she has helped those squads reach two Final Fours and one Women’s College World Series. She can be reached at: [email protected].

There are no computers, tablets, printouts floating around, or “workouts of the day” written on a whiteboard. There is only the steady hum of athletes going from rack to rack and the satisfying sound of bumper plates hitting the platforms after a successful snatch or clean. This is a snapshot of the Hatch System in action, a long-standing but still effective method of training.

Utilizing Olympic lifts and their derivatives, the Hatch System is a method of explosive training originally created for competitive weightlifting but that has become embraced for ground-based sports. It relies on Olympic movements because they involve full-body work and power production, which translate well to the field and court. As creator Coach Gayle Hatch has said, “Pure strength that can’t be converted to athletic strength is of no use to an athlete.”

Passed along to many protégés over the course of his 50-year career, the Hatch System continues to be of great use to athletes today. Teams from high schools all the way up to the professional ranks have employed it, with its success building explosive athletes at every level.

I was introduced to Coach Hatch early in my career prior to my tenure as Associate Head Strength and Conditioning Coach at Louisiana State University through colleagues who valued his system, and I’ve put his teachings to use with my own teams. This article will explain how to incorporate the Hatch System into any existing strength and conditioning program, as well as give an inside look at how we use it with the LSU women’s basketball team.

LEARNING THE LIFTS

All that is needed to train using the Hatch System is a barbell and a set of bumper plates. But the simple setup gives way to a difficult routine. Each exercise is physically taxing, and the majority of the lifts occur at or above 75 percent of a player’s one-rep maximum. The challenging nature of the system is the main reason for its success with building explosive athletes.

The Hatch System is built around a group of exercises known as the Hatch 10–the back squat, front squat, clean, clean pull, split jerk, snatch, snatch pull, 3&3, bench press, and incline bench press–with assistant exercises to complement these core lifts. The Hatch 10 exercises were selected for very specific reasons. First, most of these movements require explosive acceleration with the bar, which is essential for increasing the triple extension needed while running and jumping. In addition, each lift helps improve an athlete’s proprioception, stability, speed of movement, and functional flexibility. Because every exercise works the whole body in multiple ways, athletes get the most bang for their buck.

When teaching the Hatch System, strength coaches should begin with the back squat, which Coach Hatch considers the “king of all exercises.” It is the fundamental position for weightlifting and the most essential strength-building movement.

After the athlete is comfortable with the back squat, the strength coach can progress to the front squat. This movement adds variety to lower-body training and develops the strength and balance necessary for the receiving position of the clean, which is taught later.

Once proficient in the back and front squat, the athlete is ready to transition into the Olympic lifts. Coach Hatch recommends using a holistic instructional method with cleans and snatches by teaching the lifts as complete movements starting from the floor rather than in parts.

While breaking the exercises into parts may be easier for the athlete to digest in the short term, it can create problems down the road when melding the individual pieces into a comprehensive lift. For example, an athlete who learns the hang clean before the power clean may develop a hitch in their transition between the first and second pulls of a full clean. Though it may take more time and energy to teach a complicated lift as a whole, the payoff is a more smooth and coordinated clean or snatch overall.

The training sequence for the clean should start with the clean pull, then the power clean, and progress to the full clean while receiving the bar in a deep squat. The sequence for teaching the snatch follows a similar trajectory: start with the snatch pull and then go over the power snatch and overhead squat. The last step is to train the athlete how to complete the full snatch and receive the bar in a deep squat.

The split jerk is taught between the clean and snatch. Begin by showing the athlete the footwork for the jerk before incorporating the arm movement. When doing this exercise, the lifter should utilize the momentum generated by the triple extension to push the bar overhead–not rely on their arm or shoulder strength. Once they have the timing and movement correct, the full clean and jerk can be taught.

The 3&3, bench press, and incline press exercises round out the Hatch 10. The 3&3 consists of three behind-the-neck snatch grip presses followed by three overhead squats. Some strength coaches shy away from behind-the-neck pressing, but with proper technique and appropriate loads, it is an excellent tool for strengthening the posterior shoulder and core. In addition, the overhead squat portion of this exercise can lead to improved snatches by strengthening the receiving position. The bench press and incline bench press are not greatly emphasized in the Hatch System because they aren’t considered athletic movements, but they can be valuable in improving anterior upper body strength.

Supplementing the Hatch 10 are a variety of secondary or assistant exercises that complement the core lifts. They serve to add variety to the program, hone in on difficult aspects of the Hatch 10, or provide a unilateral way to train the body. And because the assistant exercises do not have to be combined in any particular order to be effective, they allow the strength coach flexibility in creating a training regimen.

The three-position clean and three-position snatch supplement the clean and snatch of the Hatch 10. These exercises improve jump-shrug technique and the transition between the first and second pulls. Here is the progression for the three-position clean and snatch: 1. Hang clean or snatch from the upper thigh 2. Hang clean or snatch from below the knee 3. Power clean or snatch from the floor.

Power snatches and power cleans are also important assistant exercises for this grouping because they specifically work the triple extension. Since these lifts require the athlete to receive the bar in a higher position than the traditional clean or snatch, the bar needs to be pulled to a greater height.

To add variety to the split jerk, Coach Hatch utilizes the behind-the-neck split jerk as an assistant exercise. This movement activates the posterior stabilizers of the shoulder more than regular split jerks and causes the athlete to apply force directly upward from their spine.

Assistant exercises used to augment upper-body work are bent-over rows and dumbbell presses (bench press or shoulder press, simultaneous or alternating). The row can improve athletes’ posterior upper-body strength, while the dumbbell press can develop unilateral chest and shoulder strength and stability.

Step-ups and split squats serve as the assistant exercises tasked with developing unilateral leg strength and stability in the Hatch System. For maximum results, step-ups should be performed at heavy percentages on reinforced boxes, while split squats should be done in a lunge stance with an elevated back leg.

To specifically develop posterior chain strength, improve hip hinge action, and increase hamstring flexibility–all crucial components for building explosiveness–the Hatch System incorporates Romanian dead lifts, good-mornings, and glute-ham raises. Both Romanian dead lifts and good-mornings should be performed with a straight back and legs. The bar should be kept close to the body when deadlifting and placed on the trapezius for good-mornings.

BUILDING A PROGRAM

When used in competitive weightlifting, the Hatch System is typically broken up into an intense five-day schedule with double sessions on three of those days. However, this is not suitable for college or high school athletes due to the auxiliary demands that come with being a student-athlete. For strength coaches at these levels, Hatch suggests implementing a three- or four-day lifting regimen composed of 60- to 90- minute sessions. This format allows the athletes adequate time to recover between whole-body explosive workouts.

Under this plan, one week would create a microcycle. Each day should consist of a full-body routine with a balance of pressing and pulling movements, but the strength coach should decide which specific Hatch 10 and assistant exercises are done. The day-to-day loads should be determined by the time of year, sport, positional requirements and goals, and each athlete’s ability.

A mesocycle consists of three loading microcycles followed by a fourth unloading microcycle. Mesocycles are commonly structured in a three-cycle block for optimal results. The first consists of sets of four reps for explosive exercises and sets of six reps for strength exercises at 65 to 80 percent of an athlete’s one-rep max. The second mesocycle switches to sets of three reps for explosive exercises and sets of five for strength actions in the 70 to 90 percent range. The third, peaking mesocycle drops to sets of two or less reps for explosive exercises and four or less reps for strength exercises at 80 to 100 percent of one-rep max.

This pattern of alternating through the mesocycles can be adjusted and repeated to form the yearlong macrocycle. The mesocycles can be lengthened or shortened along the way to accommodate the demands of the offseason, preseason, and competitive season.

COMMON CONCERNS

Although the benefits associated with the Hatch System are numerous and well-documented, some strength coaches are hesitant to try it. One frequently cited reason is that it focuses too much on the Olympic lifts at the expense of other important exercises. However, there is room to incorporate other activities such as plyometrics, corrective movements, and sports-specific training without deviating from the Hatch System’s core principles.

For instance, plyometric exercises go hand in hand with the explosive training aspect of the Hatch System because ground-based sport athletes need to know how to jump and land correctly. Plyometrics also give players a break from training with an external load and can help prevent injuries.

When it comes to addressing dysfunctional movements or deficits, many of the Hatch 10 and assistant exercises are similar to the actions used in the Functional Movement Screen and can provide opportunities for identifying and correcting strength imbalances. And sport-specific exercises make great auxiliary activities in the Hatch System. For sports that incorporate rotational and lateral movement, strength coaches can add work with cable machines, medicine balls, and elastic bands as assistant exercises.

Another commonly cited concern about the Hatch System is that the Olympic lifts put athletes at a greater risk of injury in the weightroom or cause players to add too much muscle. If a sport coach, athlete, or medical professional expresses this concern, a strength coach can take a modified approach to the system by removing some of the Hatch 10 exercises from their program or using simpler variations to create a system that works best for their team.

In cases where the Hatch System has already been implemented, complications can arise if athletes are physically unable to complete some of the Hatch 10 lifts. This occurs most often as a result of poor flexibility or a lack of proprioception. These are problems, however, that are easily remedied.

If an athlete lacks flexibility, strength coaches can keep their loads light and modify their range of motion, stance, or grip on the bar. For instance, if a player can’t properly pull from the floor, start with the bar on plates or blocks and gradually move closer to the floor as the athlete’s range of motion improves. If the individual has trouble gripping the bar for a front squat, have them use a wider grip or attach grip straps to the barbell.

When the player lacks proprioception, try teaching the lifts in segments using light loads until the athlete’s technique improves. For instance, a hang snatch can be much less daunting for an uncoordinated athlete to learn than a full snatch.

BRINGING IT TO BASKETBALL As the strength coach for the LSU women’s basketball and softball teams, I currently incorporate many of the Hatch 10 and assistant exercises to build explosive athletes. I teach all of the Olympic lifts and their derivatives in a similar vein as Coach Hatch, and I assign and progress the athletes’ sets and reps according to his teachings. However, I like to put my own stamp on the program by adding a circuit-training component.

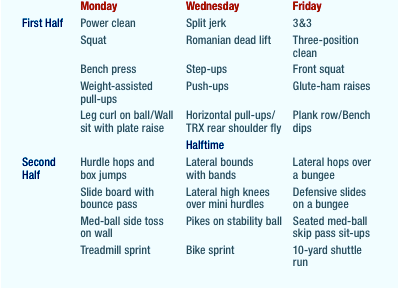

In the offseason, the basketball team has weightroom sessions on Mondays, Wednesdays, and Fridays. Our workouts are divided into two 20-minute halves with a brief three-minute “halftime” rest period in between to represent the structure of a game. The first half contains our major strength-building movements such as the Hatch 10 and corresponding assistant exercises.

The second half of our workout is a circuit consisting of five rounds of four stations. Each station requires 30 seconds of work and provides 30 seconds of recovery. Instead of including Olympic lifts in the circuit, we complete explosive lateral and rotational movements as well as sport-specific exercises, core work, conditioning, and light plyometrics. The circuit remains true to the tenets of the Hatch System by emphasizing explosive movements, but it also includes supplemental activities that develop basketball-specific agility and endurance.

In regards to periodization, we follow the traditional mesocycle format of three loading weeks followed by an unloading week. During this time, loads decrease by five to 10 percent, the players complete easier auxiliary exercises, and the circuit stations switch to 40 seconds of recovery and 20 seconds of work. As the in-season nears and team practices increase, we cut back to two days a week in the weightroom.

Built to handle a few tweaks when necessary, the Hatch System can develop explosive athletes for any ground-based sport. And by taking advantage of the Hatch 10 and the corresponding assistant exercises, strength coaches can experience the results that myself and many others have found by incorporating Coach Hatch’s program.

SIDEBAR: IN ACTION

Here is an example of how the LSU women’s basketball team uses a modified Hatch System in its offseason team workouts:

SIDEBAR: AHEAD OF HIS TIME

Gayle Hatch, architect of the Hatch System, grew up on a cattle ranch in Louisiana. Coach Hatch became obsessed with becoming an athlete early on, after his Native American grandmother gave him a book about Jim Thorpe. Eventually, Coach Hatch went on to become a standout basketball player at Northwestern State University, where many of his records still stand today.

When Coach Hatch started to strength train in high school during the mid-1950s, he was in the minority. Teaching athletes to lift weights was something few coaches were doing at the time. But Coach Hatch worked under legendary strength coach Alvin Roy, who had studied how Russian and Bulgarian athletes used Olympic lifts to develop explosive power, and would eventually become the NFL’s first strength coach with the San Diego Chargers.

Hatch’s early work with Roy set the stage for his 50-year career in competitive weightlifting and athletics. His weightlifting squads have won 53 Men’s Weightlifting National Championships and sent competitors to three Olympic teams and 12 World teams. As a result of these achievements, Coach Hatch was selected to coach the 2004 U.S. Olympic Weightlifting Team. Despite already leaving his mark on many of the top athletic programs in the country, he still coaches in Baton Rouge, La.