Jun 6, 2018Set the Bar

At Colorado State University-Pueblo, strength coach Allen Hedrick uses historical lifting averages to establish weightroom goals and guide players’ offseason programming.

I often tell my athletes: You can get strong enough, but you can never get powerful enough. What I mean is that depending on their sport and position, athletes can reach a point where further strength gains won’t benefit performance. When that happens, it’s best to shift the training emphasis from increasing strength to increasing power.

At Colorado State University-Pueblo, we have developed a system that allows athletes to make this transition seamlessly. It’s centered on a set of historical lifting averages that we categorize by sport position, and we test athletes in these lifts every offseason. Those who test below the historical averages are placed in a strength-building group, while those who test above go into a power training group. When the strength-building athletes raise their scores sufficiently, they join the power group.

We’ve been using this model at CSU-Pueblo for years with several teams, including football. On the gridiron especially, we’ve experienced great results, including seven consecutive conference championships and a national title in 2014. These, and other similar outcomes, indicate that our system is having the desired effect of maximizing sport performance.

SUPPORTING THEORY

Although we’ve had great anecdotal success dividing our players’ workouts into strength- or power-based training, there is also evidence behind it. I’ve found support for this approach through years of research.

To start, as all performance coaches know, the need for strength varies by sport and position. For example, in football, interior linemen require higher strength levels than wide receivers.

The problem is that many traditional weightlifting programs focus too much on building these strength levels. As a result, athletes spend more time improving strength than developing power.

That may not seem like a bad thing in and of itself. However, as Vern Gambetta pointed out in his 1987 NSCA article “How Much Strength is Enough?” the primary objective of a strength and conditioning regimen should be to enhance an athlete’s ability to express strength for improved sport performance. And improved performance results more from increased power than increased strength.

So if power is the ultimate goal, why don’t we emphasize it from the start, instead of initially putting some of our athletes in a strength-building group? As explained in a 2011 Sports Medicine series of reviews, it’s because there’s a fundamental relationship between strength and power. Strength is a basic quality that influences maximum power production, so an athlete can’t have high power levels without first having a good strength base.

Then, once they reach a certain strength threshold, a shift in emphasis from strength to power is warranted and will be more effective at enhancing athletic performance. Therefore, the overall philosophy behind our historical average system is to get strong to get powerful and then get powerful to be more successful in competitions.

USING HISTORICAL AVERAGES

Two obvious questions then arise: How do you know when an athlete is strong enough? And what are the optimal strength levels necessary for high-level performance? We answer these questions by collecting the historical lifting averages of our players by position. I did this for seven years before I implemented the system, and I would recommend at least five years’ of data to others. Although I have used historical averages with multiple sports at CSU-Pueblo, I’ll focus on how we tailor them specifically for football in this section.

We test all of our football athletes twice a year-once in the spring and once in the summer. At both sessions, we measure their one-repetition maximums (1RM) in clean, squat, and bench.

Using our athletes’ final testing results from their senior years, we track what the average score is in each lift by position. Each year, the averages are updated to reflect the latest testing performances by our seniors. For example, our most recent averages for the squat were 550 pounds for a nose tackle, 352 pounds for a wide receiver, and 308 pounds for a quarterback.

When we test each football athlete at the beginning of the offseason, we compare their results to our historical averages. Those who test below the historical averages go into the “standard”-or strength-group. Most of our younger players fall into this category. Athletes who are at or above the historical averages are moved to the “advanced”-or power-group.

Although there is no “good” or “bad” group, we want the athletes to be pleased if they are testing at or above the averages. If they are testing below, we tell them not to be discouraged. This is simply an indication that they need to make further progress.

When athletes are placed in the standard group, they follow that program until the next testing time. Then, if they test at or above the averages in two out of the three lifts, they move to the advanced group.

DIFFERENT PLANS

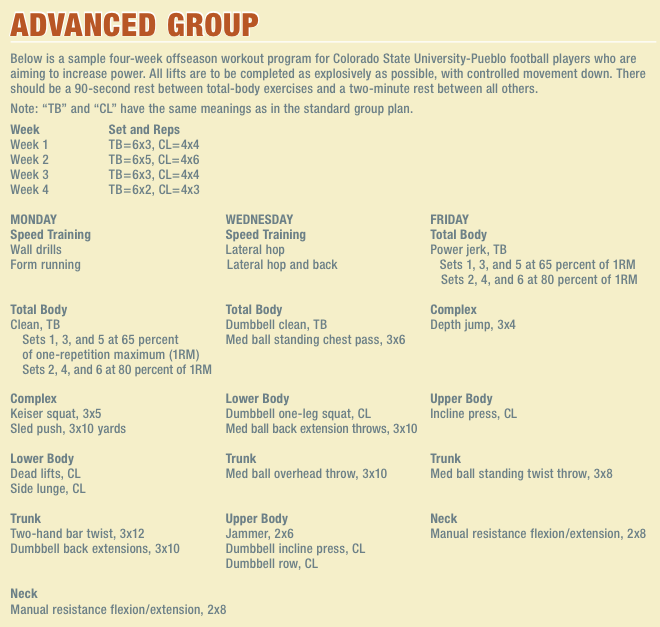

The best way to understand how we manipulate our lifting regimens to either emphasize strength or power is to compare the football workouts for our standard group (below) and our advanced group (below). These two plans are for players in one of our “big skill” positions, which comprise offensive and defensive linemen, tight ends, and linebackers.

The first difference you may notice between the two programs is that there are more weightlifting movements for the advanced group. These athletes perform the more technical clean and power jerk right off the bat because they’ve already established the correct technique necessary to do the full movements. In contrast, the standard group performs two sets of a more basic lift first on Mondays and Fridays. This allows them to establish correct technique before moving on to more complex movements. So the standard athletes will do a push press on Fridays before advancing to power jerk.

Why the focus on the Olympic lifts for the advanced group? Because Olympic-style weightlifting can produce a much greater power output than traditional exercises, such as the squat or bench press. In addition, Olympic lifts significantly improve power output against a heavy load. And as explained in a 2011 Sports Medicine series of reviews, these movements are ideal for football athletes, who often have to generate high power against heavy loads.

A second difference between the two workouts is the advanced group’s use of contrast loads for barbell weightlifting movements. For example, on sets one, three, and five for the power jerk on Friday, the load is set at 65 percent of 1RM, while sets two, four, and six are performed at 80 percent. We do this because, according to the Sports Medicine article mentioned above, contrast loads target all areas of the force velocity curve to augment adaptations across a broad spectrum. The result is a superior increase in maximal power output. In contrast, the standard group uses a nearly constant training load for all sets.

A third variation between the two programs relates to their use of plyometrics. Both groups are exposed to plyometric training to develop maximal force as quickly as possible, but the standard group performs plyometrics as a stand-alone activity.

Meanwhile, the advanced group utilizes complex training, which pairs a weightlifting movement and a plyometric activity. Athletes then perform the two exercises consecutively with little to no rest between them. Completed first, the weightlifting movement trains the muscles’ ability to produce high levels of force. Then, the plyometric activity enhances the muscles’ ability to exert force through rapid eccentric-concentric transitional movements. As a result, this method trains the neurological and muscular systems at both ends of the force velocity curve at much higher levels than traditional modalities. The result is significant increases in peak power levels.

By using historical averages to assess our players’ strength and power levels every offseason, we can get a better idea of what areas they need to improve in. Then, by splitting them into standard and advanced lifting groups, we can ensure athletes follow the appropriate program to get strong, get powerful, and, ultimately, meet our goal of enhancing athletic performance.

To view the references for this article, go to Training-Conditioning.com/References.

This article appeared in the May/June 2018 issue of Training & Conditioning.